The Mysterious Barricades

François Couperin’s piece for harpsichord Les Barricades Mystérieuses has caught the imagination of many. In these pages I discuss the piece and its title and gather its echoes in music, fiction, non-fiction, poetry, the visual arts, film, and performance.

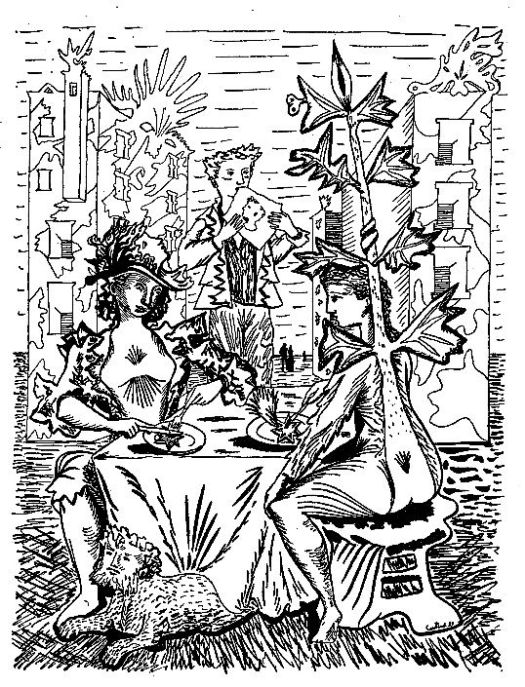

The earliest visual representation I have found that is connected with the piece or its title is a specially-made frontispiece engraving by the French artist Lucien Coutaud (1904-77) for the small book of poetry by Maurice Blanchard entitled Les Barricades Mystérieuses (1937).

I can see nothing in the engraving that evokes either the Couperin piece or the poetry of Blanchard.

A set of illustrations was made for the volume of poetry Les Barricades Mystérieuses (1946) by the young French poet Olivier Larronde (1927-65). Larronde was a protégé of Jean Cocteau. On February 1st 1945, Larronde met the artist André Beaurepaire (1924-2012) at the home of Christian Bérard, where Beaurepaire had gone to show his drawings. Like Larronde, Beaurepaire and Bérard were part of Cocteau’s circle. On their first meeting, Larronde spontaneously wrote a quatrain on one of Beaurepaire’s drawings:

The following year, Larronde asked Beaurepaire to illustrate Les Barricades Mystérieuses. The result was two lithographs, one for the cover and one for the frontispiece. The lithographs were printed at Mourlot Frères. Here are the original drawings:

Both these images seem to represent ‘mysterious barricades’ of some sort. The first, curiously, looks as if it might have made a good illustration for Blanchard’s poem, which opens with the description of someone crossing terrain blocked with people’s bones.

Beaurepaire made another drawing of mysterious barricades in 1988 inside a copy of Larronde’s poetry for Claude Arnaud, the author of a biography of Cocteau.

(Information supplied by André Beaurepaire. Images posted with his permission.)

The Cornish painter Guy Worsdell (1908-78) painted this oil painting, called “The Mysterious Barricades,” sometime in the early 1950s:

Worsdell belonged to a small set of painters based in St Ives, and was also involved in the Free Painters and Sculptors movement founded by, among others, Henry Moore in 1952. A history of the movement by Roy Rasmussen mentions Worsdell’s involvement several times. “The Mysterious Barricades” belongs to a relative of Worsdell to whose family the painter gave the painting in gratitude for their hospitality when Worsdell would stay with them during the Edinburgh Festival where it is conjectured the painting may have been displayed. Apparently Worsdell was inspired by Couperin’s music in creating this painting. (Many thanks to the painting’s owner for this information and for permission to post the painting here.)

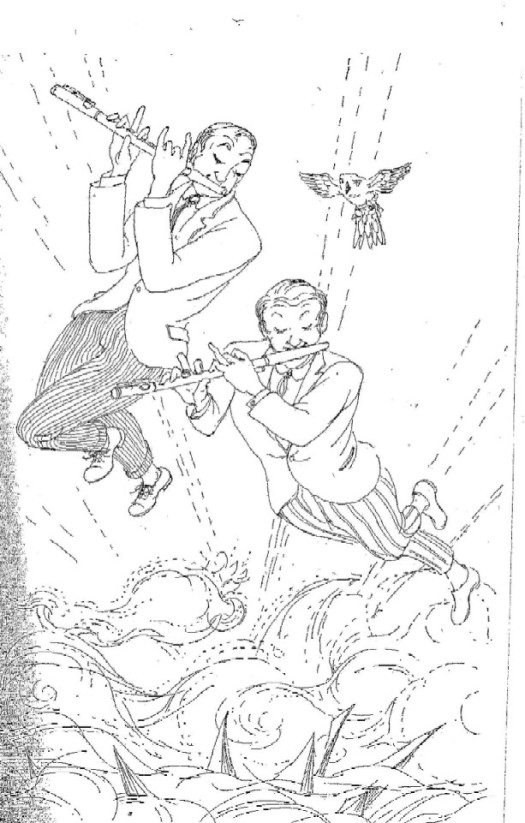

Another illustration, by Pat Marriott (1920-2002), is to Joan Aiken’s 1955 story “The Mysterious Barricades” in her collection More Than You Bargained For. Marriott’s drawing illustrates the final scene of the story in which two civil servants are inducted into The Mysterious Barricades by playing a sonata for two flutes and continuo written by one of them. The continuo is being played by the bird. The Mysterious Barricades are not themselves portrayed (I think the jagged things at the bottom are the mountain tops).

(A reader of At The Margin, vol 1, issue 9 (June 26, 2000) suggests that much of Edward Gorey’s work was published under pseudonyms and identifies the illustrations attributed to Pat Marriott for Joan Aiken’s novel The Wolves of Willoughby Chase as possible cases in point. The editors, in response, refer to an obituary of Gorey in the May 2000 issue of Locus (which I have not been able to check) that says that Gorey did the covers of “the early Joan Aiken books (as Pat Marriott).” However, in an interview of October 29th, 2001, in Strange Horizons, Joan Aiken says that “[i]n fact, Edward Gorey did not illustrate the Wolves series — in England they were illustrated by Pat Marriott… Latterly, Gorey did the jackets.” The idea that Gorey worked under the pseudonym of Pat Marriott thus seems to represent a confusion of the fact that Marriott illustrated some books for which Gorey did the covers. There is a moving piece by Aiken on the occasion of Marriott’s death in The Times of 25th October, 2002.)

In 1961, René Magritte painted “Les Barricades Mystérieuses.”

Here is the note from the Christie’s website on the occasion of the painting’s sale in 2010:

The predominant atmosphere of Les barricades mystérieuses is essentially the same one as that of L’empire des lumières, the only difference being that here it is leaf/trees that make up the most of the mysterious forest. For Magritte, L’empire des lumièreswas a favourite theme and one to which he returned repeatedly throughout his career. As he once explained to his friend Harry Torczyner, the concept of the night/day duality was one that held particular appeal for him. ‘For me,’ he wrote, ‘the conception of a picture is an idea of one thing or of several things that can become visible through my painting. It is understood that all ideas are not conceptions for pictures. Obviously, an idea must be sufficiently stimulating for me to undertake to paint faithfully the thing or things I have ideated. The conception of a picture, that is, the idea, is not visible in the picture: an idea cannot be seen with the eyes. What is represented in a picture is what is visible to the eyes, it is the thing or things that must have been ideated. Thus, what is represented in the picture L’empire des lumières are the things I ideated; i.e. a nightime landscape and a sky such as we see during the day. The landscape evokes the night and the sky evokes the day. I find this evocation of night and day is endowed with the power to surprise and enchant us. I call this power: poetry. If I believe this evocation has such poetic power, it is because, among other reasons, I have always felt the greatest interest in night and day, yet without ever having preferred one or the other. This great personal interest in night and day is a feeling of admiration and astonishment’ (Magritte, 1956, cited in Torczyner, op. cit., p. 102). The central idea of L’empire des lumières and of this painting is the impossible beauty of the concept that Breton expressed when he exclaimed, ‘If only the sun would come out tonight!’ The simplicity of this concept is added to by the organic mystery of the leaf/trees which clearly establish this landscape as being one of an alternate world, a product of Magritte’s poetic realm of the visual imagination to which he gave the name Le domaine enchanté (The Enchanted Domain). The rather reassuring presence of a smartly dressed horse and rider trotting peacefully through this enchanted landscape as if they are returning home from their Sunday ride is in keeping with the peaceful twilight atmosphere of the painting even if it does also have something of the Le Jockey perdu (The Lost Jockey) about it. Clearly a more successful reworking of the ideas outlined in his 1957 painting Le concert du matin (The Morning Concert), it is clear that Magritte himself, was evidently well satisfied with the outcome of his work in Les barricades mystérieuses. Not only did he copy it faithfully and without alteration onto the wall of the Halle Delvaux at the Palais des Congrès, but after the mural’s completion he hung onto the work and only later included it with a batch of other paintings that he gave to his dealer Alexander Iolas.

And Milton Viederman, in his “René Magritte: Coping with Loss – Reality and Illusion” (Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 35(4): 1987, pp. 983-4) writes:

The ambiguity and intermingling of night and day are recurrent themes in Magritte’s work, particularly exemplified in the series called The Empire of Lights. In these haunting paintings a night scene of a street, tranquil and without people, lit only by lamplight, is surmounted by a brilliant daylight sky. The juxtaposition of day and night, of night and day, the interpenetration of light and darkness, are reminiscent of the scene of the mother’s death, but all is transformed, calm, transfixed, without movement or change, with mystery but without manifest threat.

A variant on The Empire of Lights is The Mysterious Barricades. Once again there is an admixture or ambiguity between day and night. A warmly lighted house with a body of water in front dominates the central plan. A woman mounted on a horse approaches the scene from the left. All is still, motionless. There is a mysterious barricade-between the woman and the house? the house and the water? In a series of paintings, each called The Lost Jockey, and in other similar paintings in which jockeys are portrayed, the male rider frantically gallops from the right. It is to be emphasized that the jockey is lost. In other horseback scenes, of women, the rider approaches from the left as in the Le Blanc Seing (Blank Signet Ring), in which the rider is in an ambiguous spacial relation to the trees of the forest in which she rides. Hence, although men and women riders ride toward one another, they never meet, for they exist only in separate paintings, the barricade (a variant on the theme of the unfindable woman, to be discussed below).

Here is a photo of the mural, in place, at the Palais des Congrès (now called Square):

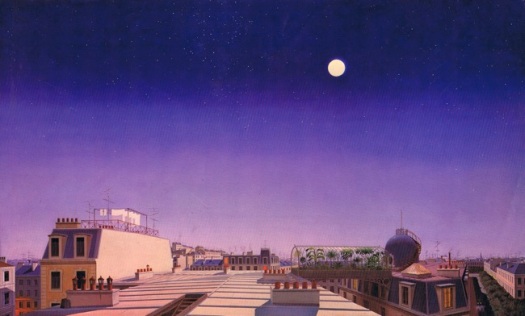

The Swiss artist, Dominique Appia, was inspired by Couperin’s piece to use the title “Les Barricades Mystérieuses” for four paintings, the first from 1968, the last from 1975. According to the artist (personal communication):

The paintings are views across the roofs of Geneva by moonlight. In some of them [such as IV, below], one can see the Cathedral and the Salève, the distinctive mountain of the Geneva horizon. I might also have depicted the music conservatory, an historical building, but I didn’t think of it at the time.

I have spent many hours on the roofs of Geneva, Paris, and New York. It is a magical place, where my imagination willingly takes off for the infinite. That’s what made me think of the title [“Les Barricades Mystérieuses”], which has struck me ever since I was a teenager.

The second painting with this title is reproduced in the artist’s APPIA (Paris, Julliard-L’Âge d’Homme, 1985) and was made into a poster (unfortunately no longer available) by Wizard + Genius of Zurich. This was the version that inspired the jazz saxophonist and composer, Barbara Thompson, to compose the “Les Barricades mystérieuses” movement of her Appia Suite (see the music page of this site). Here are the second and fourth paintings with the title (reproduced with the very kind permission of the artist).

In 1990, a Japanese-American (or perhaps Japanese) artist had a solo show at the Arras Gallery in New York. Among the items displayed is this multimedia collage, likely made sometime during the 1980s, which incorporates part of the score of Les Barricades Mystérieuses:

Here is a close up of the central panel in which the score can be clearly seen:

The identity of the artist is somewhat mysterious; this, and other works by him, are signed in Japanese calligraphy with a name that would be represented in Latin characters as Mitzo, but no further information can be found of an artist with this name (other variants have been tried). The work is currently for sale at Davenport and Shapiro Fine Arts (to whom many thanks for permission to post these pictures). I would love to hear from anyone with information about the artist.

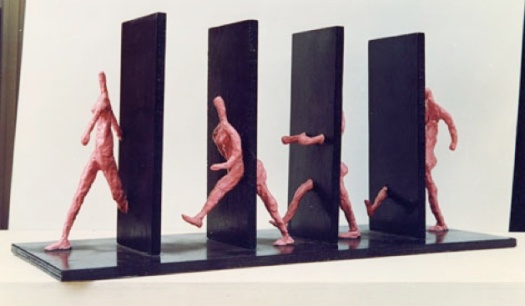

The Italian artist Lorenzo Taddei has a sculpture, made from wood and plasticine, from 1991 called Le Barricate Misteriose. The piece was inspired by hearing Couperin’s piece and, according to the artist, has “a double meaning, as a hommage to the French composer, and [since the work was exhibited in 1992 at the European Parliament in Strasbourg] as a ‘hymn’ to the dissolution of European borders and the creation of a united Europe” (personal communication). This is one of only a few instances where the barricades of Couperin’s title have been given a definitely political significance. Here are some pictures, posted with the permission of the artist:

In 1995, the French artist Sophie Ristelhueber had a photographic exhibition, at the Cabinet des Estampes of the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva, entitled Les Barricades Mystérieuses. The name seems to have been used by the gallery for a series of at least three exhibitions, of which Ristelheuber’s was the second. (The third, in 1996, was devoted to the medieval French engraver and printmaker Jean Duvet. I have been unable to find out about the first.) The following text (which I have translated from the French) was used by the gallery in its invitations to the opening of Ristelhueber’s exhibition:

LES BARRICADES MYSTÉRIEUSES

It is the title of a harpsichord piece by François Couperin which has not been definitively explained. It is at once a fluid and lyrical melody and a highly regimented structure, on which the interpreter impresses his own breathing, something that departs and returns, while always climbing. It is a form which ends where it began, a knotty brevity unfolding with the desire to endure. Here, it is the name of a series of exhibitions focussing on ancient and contemporary singularities, on accessing unanticipated spaces of knowledge and poetics, on the possibility of looking at the clear, vertiginous, beautiful and heart-breaking appearances of the world and its works.

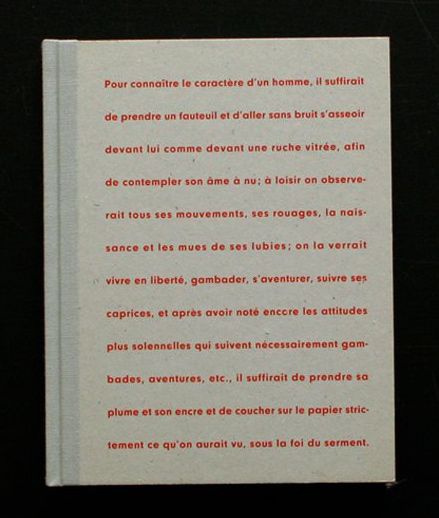

Ristelhueber says (in personal communication) that she “made hers” the name used by the gallery for its series of exhibitions. Under that title, she published the photos from the exhibition. The book’s cover uses an excerpt, in French translation, from Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy:

The text is from volume I, chapter 23, and concerns the idea of putting in people’s breasts a glass window through which to see their souls, which having been done:

nothing more would have been wanting, in order to have taken a man’s character, but to have taken a chair and gone softly, as you would to a dioptrical bee-hive, and look’d in,—view’d the soul stark naked;—observed all her motions,— her machinations;—traced all her maggots from their first engendering to their crawling forth;—watched her loose in her frisks, her gambols, her capricios; and after some notice of her more solemn deportment, consequent upon such frisks, &c.—then taken your pen and ink and set down nothing but what you had seen, and could have sworn to.

The quotation clearly speaks to the idea of mysterious barricades which, absent a window into the soul, make it so hard to “take a man’s character.”

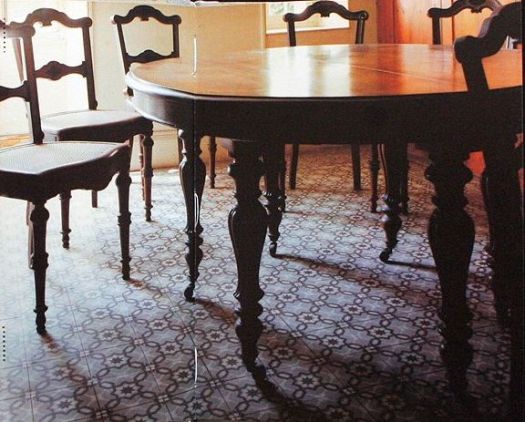

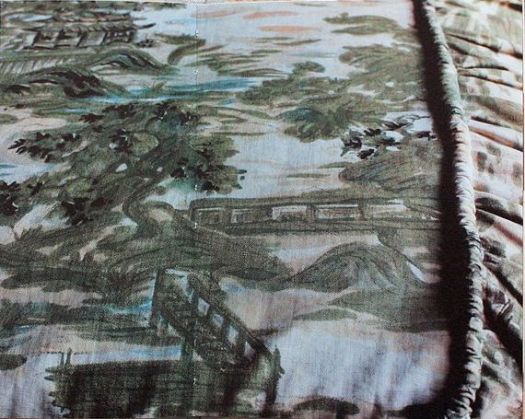

Here are a couple of photos from the collection (posted with the permission of the artist):

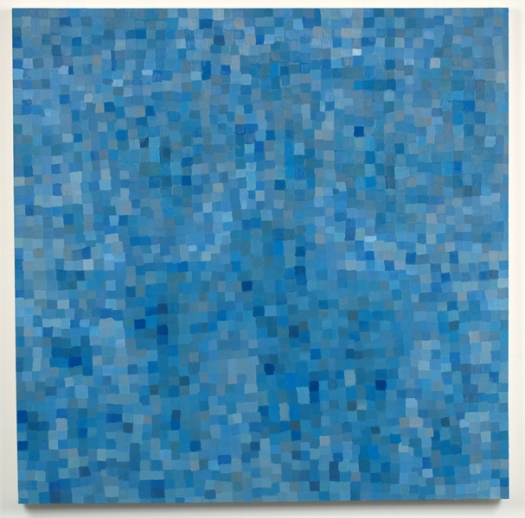

William Andrews, director of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, entitled this painting “Mysterious Barricades” (oil on canvas 48″ x 48″ 2003; reproduced with the permission of the artist):

Here is the description Andrews provided for it when it was exhibited around 2003-4:

Apparently when you play [“Les Barricades Mystérieuses”] on the piano, your hands never need move from their original position. It is as if there is an invisible barrier and your hand position is fixed. I equate this to the boundary of the canvas. Of course your hands could move beyond the boundaries of the piano or canvas, but then you’d no longer be producing music or paintings. (I would alter that now [2006] to say you’d no longer be producing visible or auditory effects.)

These paintings show the difficulty in grasping a heavily textured idea in two-dimensional form using self-constructed barriers like the specific size of a canvas or the use of many permutations of a single color. So these are like polyphonic paintings that are constructed as machines to overcome the imaginary obstacles of the paint, the brush, the canvas, and the artist.

The British artist Chris Jennings has worked a lot on the relations between visual art and music. Himself a harpsichordist who studied with Jane Clark (the author of a work on Couperin whose theories about the origin of the name Les Barricades Mystérieuses are quoted on this site), Jennings writes of

the personal experience of the relationship between the reading of the ‘text’ of music, the subsequent performance (manufacture) of that text into the initiation of sound, and the ‘point of production’ in the manufacture of a painting; the sustaining of line and form within both practices. I very much liked the insistence/persistence of [Couperin’s] motif (particularly essential on an instrument without a sustaining pedal (rigorous fingering!), the elaboration of the ‘voices’ through which the motif remained discernable.

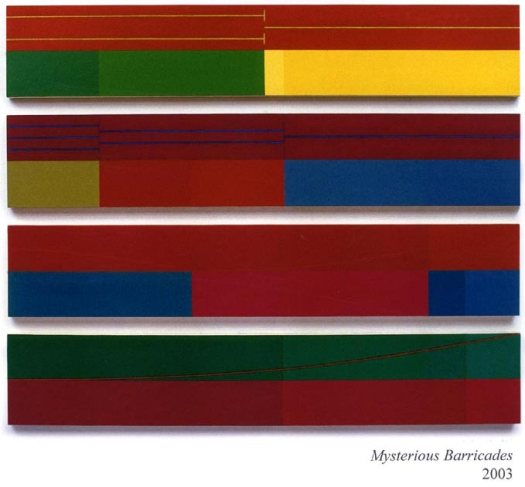

In 2003, Jennings painted a series of four paintings under the collective title The Mysterious Barricades. They are here displayed vertically although the artist notes they should ideally be displayed horizontally to “reinforce the horizontal and developmental nature of the work, the elasticity but continuum through space and time”:

About these paintings, Jennings writes:

The upper half of each painting contains a linear and proportional division of the canvas. The lower half of each painting contains a ‘leap-frogging’ of colour development, an overlaying of colour transparency (persistence, revelation but concealment: the Mysterious Barricades?) and very close juxtaposition of close toned colour (I hope subtle friction, but difficult to see in the web images). In this work I have attempted to deal with the awareness of ‘where I’ve been/where I am now/what’s coming next; ie. the integration of the moment of application, memory and anticipation, so important in the reading of both painting and the text of music.

(Many thanks to Chris Jennings for permission to post the work and for all material quoted here.)

The Icelandic artist Arngunnur Yr uses the title “Les Barricades Mystérieuses I” for this 2005 painting (oil on panel, 39″ x 48″; reproduced courtesy of the Hosfelt Gallery, SF/NY):

Further paintings in the series “Les Barricades Mystérieuses” (2005-6) can be seen at the artist’s website. About this series, Maria Porges, in an essay “Going for Baroque” from an exhibition catalogue (2006) of Yr’s work, says:

Yr’s pictures of cloudy, meditative skies invoke pleasures both contemplative and sensual. Like the celestial scenes artists once painted on the ceilings of churches and palaces, her images offer us views into an idealized place—minus the naked cherubs and gracefully-draped angels. Yr’s clouds vary only slightly from painting to painting, more a poetic description of her subject than a record of specific meteorological events. Ropy puffs of softly brushed grey lightly tinged with blues, yellows and pinks recede into the distance. Filling the frame, they become the subject, verb and object of these canvases, all of which are titled Les Barricades Mysterieuses— the Mysterious Barricades. Yr, who trained as a flautist before turning to art, borrowed this name from a musical composition by Francois Couperin (1668-1733). In this short Baroque work, the notes are flowing and hypnotic, as the same melodic phrase and variation repeats several times. It’s not certain what Couperin meant by his title, but clouds are by their very nature “mysterious barricades,” so it is apt for Yr’s pictures. Those who believe in an afterlife are confident that they know what lies beyond that mystery. The rest of us, Yr seems to be reminding us, are not.

British photographer Mike Chisholm has produced a series of twelve photographs called “The Mysterious Barricades” (2008). He writes that the title of the piece “will resonate for anyone who has felt the frustration of obstruction by unseen barriers.” Here are a couple of the photographs, reproduced with the permission of the artist:

An anonymous piece of graffiti in Paris makes a mysterious referece to the title of Couperin’s piece: “Fin des temps pacifiés: Barricades Mystérieuses” (“End of peacetime: Mysterious Barricades”). Here is a photo taken by Roman Schmidt and posted in his blog with the description:

Barricades mystérieuses à Paris

24 juillet 2009, 10h24, place Robert Antelme, Paris 13ème

And here is another photo, some months later and taken at night, with the addition of a tag on the right:

The photo is by Lucy Macnab who posted it, on 25th January 2010, on the GPS (Global Poetry System) site published by the Southbank Centre in London. She also provided this text:

I’m not at all sure what this means – the end of pacified time, mysterious barricades – but I like it. Found near a very new part of Paris, a board on one of those spindly new trees that are planted in the middle of huge new developments. Former flour mills have been converted into office space, with some residential, some of the university and an art space: www.betonsalon.net I guess sometimes poetry can give you a feeling or a meaning even without a literal or logical understanding of what it means. The little wooden tree trunk against the gleaming lights of the massive buildings all around only added to the meaning I found in this poem.

(Photos and text posted with the permission of their authors.)

The photographer Sarah Loven has a series of photographs with the general title Marie Antoinette – The Rendezvous (2010). One of those photos bears the name “Les Barricades Mistérieuses”. The artist is evidently picking up on the idea of the mysterious barricades as masks. The Marie Antoinette connection is also made by Kathryn Davis in her Versailles: A Novel and Sofia Coppola in Marie Antoinette.

(Photo posted with permission of the artist.)

In a great “meta” twist, the French artist Le Gentil Garçon (The Nice Guy), in 2011, exhibited an installation that is like an embodied form of this webiste. The following excerpt from the artist’s encyclopedia Tout le Gentil Garçon (2011) explains the nature and origin of the work.

The Mysterious barricades

[micro-architecture and documentation 2011] one-off piece ; 1,984 elements in wood, reproduction of a painting, books, CD player ; 530 x 270 x 250 cm

The path is blocked by a strange construction of piled-up square-section pieces of wood arranged according to a method inspired by a popular gizmo from the 1980s – a sort of “pin board” that was used to reproduce forms. The surface of the wooden wall seems to have been modified to follow the outlines of different objects that have found refuge there: a reproduction of a Magritte painting, a number of books, a framed photo and a CD player. There is also an alcove with a table and two seats for the consultation of the different documents.

Etymology: Before being the title of a work by The Nice Guy, The mysterious barricades was that of a piece for harpsichord by Couperin, 1717, a book by Edmond Jaloux, 1922, a poem by Blanchard, 1937, a collection of poetry by Olivier Larronde, 1946, a sentimental novel by Jacqueline Bellon, 1960, a painting by Magritte, 1961, which served as a model for a fresco in the Palais des Congrès in Brussels, an ethnological work, 1988, a piece of music for flute and orchestra by Luca Francesconi, 1989, a detective novel by Sébastien Lapaque, 1998, and an exhibition of photographs by Sophie Ristelhueber in Geneva, 1995.

Origin: The Nice Guy was invited to create an ephemeral open-air work for a group exhibition on the concept of territory. After various digressions, he became interested in barricades as precarious constructions that can demarcate and protect an area during riots. He then had the idea of a barricade with a front side that would mimic the architecture of resistance, and an unexpected, mysterious back. Without even knowing what the work would consist of, he thought of a title for it: The mysterious barricades. As is often the case when he comes up with a title he particularly likes, he looked at what it might mean, and tried to find out if other artists, short of inspiration, might not have stolen it from him before he himself invented it. Exceeding his hopes, and retroactively, this search itself went to the heart of the project. And he now realised what his barricade had to contain: a space for the presentation and consultation of all these namesake works.

Semantics: How did the title become so popular, and keep spontaneously reappearing? Olivier Larronde, for example, did not know Couperin’s rondo. Quotation, reinvention, tribute: homonymy marks out the territory of an imagination round which artists’ thinking circulates freely.

It is striking that the artist should have ‘rediscovered’ the name “les barricades mystérieuses” ab novo. Another interesting feature of this account is that it represents one of the rare assocations between the barricades of Couperin’s composition and the barricades as icon of revolution or political unrest. I have found this connection only in the note by the poet Henry Weinfield on his use of the name The Mysterious Barricades for the poetry journal he edited in the 1970s, and in a brief reference in Alejo Carpentier’s novel Los Pasos Perdidos. (The musicologist Wilfrid Mellers notes that the term “barricades” in French came to have its revolutionary resonances at least since 1648. Indeed, the piece Les Baricades by Chambonnières, written in 1649, probably refers to a revolutionary use of barricades in the “journée des barricades” of 1648.)

Here are some photos of the installation (taken by David Gagnebin-de-Bons), which was exhibited in Bex, in Switzerland. (Photos and text reproduced with the permission of Le Gentil Garçon.)