The Mysterious Barricades

François Couperin’s piece for harpsichord Les Barricades Mystérieuses has caught the imagination of many. In these pages I discuss the piece and its title and gather its echoes in music, fiction, non-fiction, poetry, the visual arts, film, and performance.

On July 1st, 1907, Marcel Proust organized a dinner and concert. He himself chose the programme of music for piano or violin and piano, and it included works by Fauré, Chopin, Beethoven, Liszt, Schumann, and Chabrier. It also included Couperin’s Les Barricades Mystérieuses. (The details of the programme are given by Jean-Yves Tadié, on p. 487-8 of the English translation of his Marcel Proust: A Life.)

Edmond Jaloux (1878-1949) published a book Les Barricades Mystérieuses (Paris: Bernard Grasset) in 1922. I conjecture that Jaloux composed this short novel as an attempt to recreate in words the sensibility he found in Couperin’s music. The book tells the story of Guy, Wanda and Martial, as narrated by a reminiscing Guy. He and Wanda grew up as neighbors and friends. When, as a young man, he introduces his friend Martial to Wanda, they fall in love. Guy does everything he can to promote the romance. When Wanda announces to Guy that she and Martial will get married, it becomes evident to Guy that he loves Wanda. Eventually, Wanda becomes bored with Martial, breaks of the engagement and begins a romance with Guy. Early on during these events, Wanda plays to Guy Les Barricades Mystérieuses:

Wanda led me into the drawing room. She sat down at the piano, threw out a few chords at random, and then I heard the strains of one of my favorite pieces: The Mysterious Barricades. Never had Couperin’s strange music squeezed my heart so much. Those treacherous and melancholy phrases, which revolve endlessly on themselves; those appoggiaturas, which give such a sense of incompleteness; those capricious resolutions that resolve nothing and which, from their gracious knot, instantly let new garlands of crystalline sound unroll; that softness and those desires, almost gallant and almost funereal; all that enveloped me and rendered me numb. Something mysterious isolated me and cut me off from the world. A kind of reverie, heavy and deadening, stole over me, paralyzing me bit by bit. Life appeared to me through a mist, dancing and blurry, and like the golden robe of a dancer seen on the other side of a river, surrounded by fog and all mixed up with birds, with grains of wheat, with clouds of incense, with gusts of leaves. Persistent images of love, which burned my eyes; longing for an unknown sun; desires for an undying woman, more beautiful than all earthly roses; a dance of the still feeling dead, floating under the cypress trees of a cemetery, while the circling owl spots in the distance a vole, or the moon, or the return of a drunken porter.

I saw the day depart for the West, sliding along a purple, sandy path; I saw the night approaching from the East, running along already black paving stones. I saw the heavenly blacksmith hang a star from the void of his workshop – first one, barely burnished, then another, better finished, like a sparkling pendant. I closed my eyes. Wanda was silent for a long time.

– Well?

The sound of a human voice made me shudder. Mlle de Vionayves put her hand on my shoulder. (28-30)

Later, the romance between Guy and Wanda also begins to go wrong. Another performance of the Couperin emphasizes its mournful qualities:

That same evening, she took herself to the piano and played again, I don’t know why, The Mysterious Barricades of Couperin which she liked so much and which I too liked ordinarily. Why, that day, did I experience a sense of ill-being, of indefinable anguish? There was the same, secret numbness that the music brought on, the same paralyzing fascination. One could have listened to it for a long time without daring to tear oneself away or regaining one’s freedom. Rings of fleeting pleasure, of straitened melancholy, unfurled without end. The music came and went like a raft gliding from one bank to another, carrying nothing but sundered couples, lovers dead or separated. Listening to it, it was as if I saw, at the bottom of an old garden, musty and dilapidated, endless walls of roses, their bases pulpy and powdered with gold, their moving terraces the color of gold, or of nymphs. It was as if these roses threw up an impenetrable wall between ghosts, perruqued or in hoop-skirts, whose arms stretched towards, but never reached, each other across the abundant hedges, their uppermost twigs both spiny and flowered. After many reprises, I was tempted to get up, to beg Wanda to stop, but I stayed put in my armchair, inert and as if indifferent, exhausted by the languor of that smooth and weakening music.

– Well? said Wanda when she had finished, what’s wrong with you, Guy, you seem completely crushed.

– I don’t think much of that music. It destroys me.

– It doesn’t take much to do that! Me, I like it better and better. I shall end up playing nothing but Rameau, Couperin, Daquin and Dandrieu, but Couperin is the one I prefer to all others. When I listen to him, it seems as if I am no longer a silly girl of today, with the ridiculous fads of the young, but that I am living the delicious life of the 18th century, that I get my hair done at the Belle-Poule, and wear hoop-skirts three metres wide, and go visit Mlle de Lespinasse or Mme d’Epinay.

– Alas, I said, I too wish things were like that. Perhaps, after all, it is that regret that makes me so sad when you play that piece! (88-90).

Finally, Wanda breaks off the engagement with Guy too. She explains:

I hid the truth from you for as long as I could, I made superhuman efforts to play my part in your comedy. One day, I just couldn’t keep it up… There is some sort of mysterious barrier in me that stops me from ever being happy. My will has nothing to do with it…(100).

Wrapping up the whole sorry story, Guy concludes:

Well, there’s the sad story that goes through my mind whenever some old almanac informs me that it is the 1st of June, or when, by chance, the morbid, disturbing or languorous strains of Couperin reach my ears. But with time, I’ve ended up hating all music. (105-6).

The translations above are my own (with advice and help from Marc Brudzinski). The French is very overwrought and defies easy translation.

Also in 1922, over in England, a reference to the piece, and its title, appeared in The Worm Ouroboros by E. R. Eddison:

She put up a finger. “Hark,” she said. “Your daughter playing Les Barricades.”

They stood listening. “She loves playing,” he whispered. “I’m glad we taught her to play.” Presently he whispered again, “Les Barricades Mystérieuses. What inspired Couperin with that enchanted name? And only you and I know what it really means. Les Barricades Mystérieuses.”

In this connection, it is interesting to look at the comment on the Couperin piece by composer Luca Francesconi, quoted on the Music page of this site: “infinite, interminable, with neither head nor tail.” Is not this exactly what the symbol of Ouroboros, the serpent that eats its own tail, is supposed to signify?

In this connection, it is interesting to look at the comment on the Couperin piece by composer Luca Francesconi, quoted on the Music page of this site: “infinite, interminable, with neither head nor tail.” Is not this exactly what the symbol of Ouroboros, the serpent that eats its own tail, is supposed to signify?

While this may not be the answer to what inspired Couperin with the name, it may, if Eddison heard in the piece what Francesconi does, explain why he invoked it at the beginning of this novel. (In fact, the ‘enchanted name’ seems much more apt as a description of the sensibility of Eddison’s other three novels, the Zimiamvian trilogy, which thematize the notion of separation and disjuncture.)

Glyn Daniel (1914-86)  had an illustrious career as an archaeologist at St. John’s College, Cambridge and was also active in extending research in archaeology to a wider audience through publications, radio and television. He was well-known as the chair of a panel of archaeological experts on the television show Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? through the mid-50’s. In addition to his archaeological activities, he published two mystery novels: The Cambridge Murders (originally published in 1945 under the pseudonym Dilwyn Rees) and Welcome Death (1954). The novels feature, as amateur sleuth, a Cambridge archaeology professor Sir Richard Cherrington. Sir Richard is a don at an imaginary college, Fisher College, located between St. John’s (Daniel’s own college) and Trinity. Various sources state that Sir Richard is based on Daniel himself. However, Norman Hammond (American Antiquity 54(2), 1989, p. 237) rather more authoritatively tells us that the character was modeled on fellow archaeologist – and Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? participant – Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Sir Richard’s age (relative to Daniel’s at the time of the novels’ composition) and his peerage suggest Sir Mortimer; his academic location, a Cambridge college “next to” St. John’s, suggests Daniel. Perhaps the safest conclusion is that Sir Richard is a composite figure, drawing on both these models.

had an illustrious career as an archaeologist at St. John’s College, Cambridge and was also active in extending research in archaeology to a wider audience through publications, radio and television. He was well-known as the chair of a panel of archaeological experts on the television show Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? through the mid-50’s. In addition to his archaeological activities, he published two mystery novels: The Cambridge Murders (originally published in 1945 under the pseudonym Dilwyn Rees) and Welcome Death (1954). The novels feature, as amateur sleuth, a Cambridge archaeology professor Sir Richard Cherrington. Sir Richard is a don at an imaginary college, Fisher College, located between St. John’s (Daniel’s own college) and Trinity. Various sources state that Sir Richard is based on Daniel himself. However, Norman Hammond (American Antiquity 54(2), 1989, p. 237) rather more authoritatively tells us that the character was modeled on fellow archaeologist – and Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? participant – Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Sir Richard’s age (relative to Daniel’s at the time of the novels’ composition) and his peerage suggest Sir Mortimer; his academic location, a Cambridge college “next to” St. John’s, suggests Daniel. Perhaps the safest conclusion is that Sir Richard is a composite figure, drawing on both these models.

The novels are said to be of the Van Dine school of mysteries. Like others of the school, “Daniel writes about the intelligentsia, with wit and sophistication. The Cambridge Murders is at its most charming when it is recreating traditional life within that school. Like the Van Dineans, Daniel produces a very complex plot whose chief interest is its storytelling as a whole, complete with a multitude of rich detail. In the Van Dine school tradition, Daniel is especially interested in the movements of the suspects around the murder scene at the time of the crime. These are looked at exhaustively, and one can follow them with a map of the college. Also like Van Dine school writers, Daniel likes to get new perspectives on such movements, new approaches that bring to light hidden patterns. Daniel also follows Van Dine school tradition in having a number of pleasantly surreal touches deck out his story” (Mike Grost).

In the late 1940’s, Daniel composed a draft of another Sir Richard Cherrington mystery, entitled The Mysterious Barricades. The novel was never published, but the draft is in the Daniel archive at St. John’s College, Cambridge. In this novel, Sir Richard is in India, delivering a series of archaeological lectures during WWII. The background for the plot is provided by British Intelligence in Delhi. In fact, Daniel served in British Intelligence in India during the war so, as with the academic setting of The Cambridge Murders, we can be assured of a certain authenticity.

Besides supplying the title, Couperin’s Les Barricades Mystérieuses plays an essential role in the novel. On his way to Delhi, Sir Richard spends the night at the Sind Hotel in Karachi. In the room next door, a young soldier, Chandler, whom Sir Richard had befriended during their several-day journey from England is murdered. Chandler was going to Delhi to start working for British Intelligence there. So when Sir Richard arrives in Delhi, he continues to investigate the murder. The plot of the novel is typically complex. In the broadest strokes, it turns out that Chandler recognized someone in Karachi who wasn’t supposed to be there and so had to be silenced. The malefactor had been working himself for British Intelligence in Delhi, but as an Irishman with a grudge against Britain, he was actually spying for the Japanese. The investigation becomes intertwined with another, older murder near Delhi, in a place called Murree. (There is evidence that the novel was originally to have been called The Muree [sic] Murder.) This was done by the dead man’s wife and her lover. The Couperin piece becomes relevant to the Murree murder, though this only emerges gradually. (Fans of The Cambridge Murders may be pleased to learn that Giles Farnaby also turn up in Delhi for a small role in the novel.)

Here is Sir Richard, discussing Conningsby, one of the intelligence officials with Anne Longford, the friend, and perhaps more, of Chandler:

“By the way,” he went on, “he has one little nervous trick which also gives him away.”

“What’s that?”

“Haven’t you noticed? He whistles softly a little tune under his breath, on occasions.”

“I’ve noticed once or twice. That’s quite true.”

“Have you noticed it is always the same tune?” asked Cherrington.

“No, is it?”

“Yes. I don’t suppose he knows what it is himself. He always whistles a snatch of the same tune, just as other people nervously doodle on a sheet of paper in the same way, or make the same gestures with pencils or spectacles when they are thinking of something else. The interesting thing is that it is a tune I know but can’t for the life of me place. All I know is that there is something wrong about the way he whistles it and that it is well known to me.”

“What sort of tune is it? A dance tune ?”

“No, not a modern dance tune” said Cherrington. “It’s an old melody – the sort of thing you might get in some harpsichord music. I could easily track it down at home. It’s not Byrd or Bull or Gibbons or any of the English composers: I feel sure it is some early continental composer- Scarlatti or Rameau perhaps or someone less well known like Buxtehude or Pachelbel or Frescobaldi. I don’t know.”

“But it is very unlikely Conningsby would know any music by early classical composers.”

“Is it?”

“Most certainly. I know he has no classical musical knowledge at all. He is only interested in swing music.”

“That’s very curious. I doubt if I am wrong in this matter. After all I have only seen the man close to twice but it was a haunting little tune, and as I say somehow changed since I last heard it. I am sure that if I had my own music library of early keyboard composers available I could track it down at once.”

“Does it really matter?”

“No, I suppose not” said Cherrington readily. “Just my insatiable curiosity. I like to be able to label correctly all the strange facts I note.”

“Well,” said Anne. “If you. really must track this tune down, though to me it seems a waste of time, I expect we can easily do so.”

“How?”

“I’ve made friends with an old bachelor who lives out on the ridge beyond Delhi and who has a very large collection of music, both scores and recorded. I know he is interested in the primitives and if you like we will go out there and see him. He’s a very charming person: ex I.C.S. but retired early in the war and is staying out here rather than go back in the middle of the war. I don’t blame him – he has a lovely house and plenty of servants and good food, and there are no relatives for him to go back to in England.”

“What s his name?”

“Cooper. Sir Francis Cooper.”

Sir Richard stopped in his tracks and seized the girl by both hands. “If I weren’t such an old man and if my nephew Giles wasn’t eyeing us suspiciously from our table over there, I should kiss you with delight” he said.

“But why?”

“Your mention of this charming person Sir Francis Cooper, whom we must certainly go and meet, has jogged my memory. I have no doubt that the tune which Wing Commander Conningsby whistles occasionally is a dance by Couperin, although at the moment I cant remember what it is called. Do take me to meet your friend as soon as convenient.”

“I will indeed. And now we must join the others. Giles is looking very savagely at you.”

It was not until the following Monday morning that Cherrington and Anne Longford were able to go out to Sir Francis Cooper’s house. She had been on duty all day Sunday and Sir Richard was busy on Sunday evening putting the finishing touches to his Monday morning’s lecture…

“Anyhow here we are. I should warn you,” said Anne as they went up the drive, “that you may find Francis a little absentminded or peculiar. He’s a bachelor and has lived a lot out here by himself. Despises the present British administration as effete and spineless. But he is really a dear and very kind and gives gramophone concerts every week to which officers and other ranks can come. I was going to one when I called to see you last week.”

Sir Francis Cooper greeted them affably enough although he was persuaded that Cherrington was a man from the Ministry of Economic Warfare who was supposed to be coming out to see him that morning. “It is only fair to tell you, my dear sir,” he said “that my information is likely to be out of date. It is a long time since I dealt with problems of rubber and rice – yes a very, long time.”

While they were talking Cherrington looked appreciatively round the large room into which they had been shown – exquisitely furnished, booklined, the floor covered with Persian rugs, housing two grand pianos – it was such a room as he would like to inhabit himself. His heart warmed to the slightly donnish figure of Sir Francis.

It took them several minutes to explain to Sir Francis why they had come. “But whatever does the Ministry want with early piano music?” he asked and then looked craftily and wagged his finger at them. “I see now” he said. “It’s some special code. There’s no need to tell me. I saw that excellent film “The Lady Vanishes”. I fully understand. My library is at your disposal.”

They thought it better not to protest and it was not long before Cherrington, with an exclamation of triumph took over a volume of Couperin harpsichord suites to the piano and began playing quietly. As Anne Longford listened she remembered having heard the tune once or twice before; it was a rondeau with a refrain which at, times sounded lively and gay, at others sinister and dark. Or was it that Sir Richard, whose playing she admired at once, was putting some sinister content into his execution of the tune. She went over to the piano and Cherrington turned to her .

“This is it,” he said, smiling “Les Barricades Mysterieuses.”

“Pleased at tracking it down?” she asked, “your vanity satisfied?”

He stopped playing and his face was puzzled. “I’m just wondering,” he said “why Wing Commander Conningsby whom you tell me has no interest in classical music, whistles this rather obscure tune, and why he always whistles it out of tune and time”. (58-60)

Sir Richard mentions Conningsby’s tick to some of the investigating police officers.

“You might ask him another question,” said Cherrington. “Ask him why, when he is nervous or excited, he whistles to himself, and slightly out of tune, the melody from Couperin’s Les Barricades Mysterieuses.”

The other three stared at Cherrington uncomprehendingly; indeed Sir Richard was rather puzzled himself why he had said what he did. (90)

In due course, a witness, a young soldier trained in classical music, comes forward with testimony that indicates a man walking away from the scene of the Murree murder was whistling a tune. This leads to suspicion falling on Conningsby as the murderer in that case. The actual villain, though, was too clever by half. Sir Richard interviews the witness:

“Sergeant Whiting?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So good of you to come up and see me. Cigarette?” Sir Richard held out his case and gave the young man a light. “I expect you are wondering what it is all about.”

“I am rather.”

“My name is Cherrington, Sir Richard Cherrington.”

“Yes. That is what the Squadron Leader in the Secretariat said.” He hesitated. “Were you at Cambridge, sir?” he asked.

“I was,” said Cherrington. “And still am there normally. I have been lecturing at Delhi University and am about to go back to Cambridge.”

“I thought I had seen you about,” said Whiting. “In Trinity Street and in the bookshops and at concerts.”

“You were an undergraduate were you?”

“I had finished my degree and taken the Mus. Bac. just before war broke out,” went on Whiting. “I was in the middle of my course at the Royal College when I was called up.”

“Did you study the organ at the College?” asked Cherrington.

“Yes.”

Cherrington walked over to the piano and sat down on the piano stool. “Did you. ever play the harpsichord?” he asked. “Or were you particularly interested in early keyboard music?”

“Bach of course,” said Whiting, “But my especial love was modern French organ music.”

Softly, quietly Sir Richard began to play the piano. He did not look at Whiting as the haunting melody of Les Barricades Mysterieuses grew under his hands, first gravely and then gaily, the tune at one moment bright and happy, at another recurring dark, sad and sinister. When he had finished and only then, he turned to the other man and asked, ill concealing the excitement he felt, “Do you know that tune?”

“Oh yes, it’s familiar to me all right, but I don’t know the name.”

“I see. Have you heard the tune recently?” Sir Richard made the question sound a matter of routine

Whiting was puzzled. “Yes I have,” he said. “But for the life of me I can’t think where. I’ve been so busy in the last few months organising concerts and running the orchestra. Should I know the tune ?”

“Not necessarily. It is actually a rondeau from a harpsichord suite of Couperin.” “Couperin, yes. Yes”

“A rondeau called Les Barricades Mysterieuses” went on Cherrington.

“I’ve heard of it yes, and have heard it several times. Probably at concerts in Cambridge.” He paused. “And yet the tune is somehow familiar to me. I’ve heard it recently. Why do you ask? Why have I been sent for, sir? Is there some mystery behind all this?”

“Indeed there is a mystery,” said Cherrington easily. “The mystery is why Couperin gave this title to his dance. Les Barricades Mysterieuses – the mysterious barricades. To what mysterious barricades did he refer ? Is it a tune of hate or love, a love song perhaps symbolising..”

“Walt a minute, wait a minute.” Whiting was on his feet. “You have set my mind going. A love song, of course, that is it. Now it all comes back to me.”

“You heard the tune in Murree in June,” said Cherrington, softly.

“Yes. How the devil did you know? What is all this about?”

“Under what circumstances did you hear this tune ?”

“It was the night that the Colonel was murdered and the bungalow burnt down. I expect you have read about the Murree case, haven’t you? It attracted a deal of publicity at the time.”

“I have read about it” said Cherrington, with studied understatement.

“I’d been taking a friend of mine, a girl I know,” he blushed. “Well, actually I’m going to marry her,” he hurried on. “She was staying at the leave camp at Lower Topa and I was staying in Murree. I took her to a dance at Sams and we went for a walk afterwards along one of those little hill paths. Do you know Murree, sir – I don’t suppose you do?”

“I have been there once.”

“I see. I don’t know why I am telling you this,” said Whiting. “Except that I don’t know why you played this tune to me. We sat on a bench on one of the hill paths and looked out over the valley towards Pindi – it was a quiet moonlight night. We hadn’t been there long when a man in RAF uniform came along the path. The path was in shadow so that I couldn’t see him clearly: I never saw his face clearly nor could I tell what badges of rank he was wearing. What I did notice was that he had very large moustaches and was smoking a cigar; but what attracted my attention was the fact he was whistling a tune – the tune you have just played to me.”

“Are you sure of that?”

“No doubt about it at all. I noticed it because it was an unusual tune: one doesn’t expect to see RAF officers going around whistling tunes from harpsichord suites. As I know now he was whistling it very well.”

“You can swear to that?” Cherrington looked at Whiting keenly.

“Oh yes, I can. I think I have a really good aural memory.”

Cherrington began to play again. It was difficult to do what he wanted, but by playing carefully chosen wrong notes and altering the time, he managed to convey the impression of the air out of time and tune as he had heard it whistled by Conningsby in his office. He stood up and went over to Whiting.

“That wasn’t quite the same, was it?” said Whiting. “I mean you had done something very curious to it? Why was that ?”

Cherrington spoke slowly and deliberately. “I want you to answer this question most carefully,” he said. “I have played you Couperin tune twice – the first time as it should be played and the second as you say, having done something curious to it. Which way did you hear it whistled that night in Murree?”

Whiting did not hesitate a moment “The way you first played it, sir. There can be no doubt about that.”

“You are absolutely sure?”

“Absolutely sure. Is it important?”

“Very important. Very important indeed.”

“So it was in connection with the Murree murder that you sent for me?”

“It was but I couldn’t put the circumstances of that night into your mind before I played you the tune. I hoped the tune would start a train of thought in your mind and lead you to the Murree murder and I was fortunate.” He paused.”The murderer was less fortunate. It was bad luck that of all the people who saw him that night, it had to be you – a trained musician. Yes, I can sympathise with him, almost. And yet,” went on Cherrington, “he was not thorough, not careful enough. It is indeed difficult to carry out a perfect murder which is carefully premeditated.” (147-9)

So Sir Richard infers that the hapless Conningsby is being framed for the Murree murder. While Conningsby is still under arrest, he is visited by Sir Richard and the police officer Henley:

Conningsby went over to the window of the little room in which they were interviewing him, and looked out into the courtyard. Softly he began to whistle, nervously and jerkily, and half under his breath. Cherrington caught the lilting melody of Couperin. It was out of tune and time but, distorted though it was, there was no doubt it was still Les Barricades Mysterieuses.

“Tell me Conningsby,” asked Cherrington. “Why do you in moments of stress always whistle that little tune under your breath?”

Conningsby turned round, startled. “What tune?” he asked.

“What you have just been whistling.”

“Oh that? I hadn’t noticed it was always the same tune. That particular tune has been buzzing around in my head for a long time. I picked it up in Ceylon when I was stationed in Kandy. I had a room next to a man who was very musical but had very few records. He used to play this tune a great deal. He told me once what it was.”

“A rondeau by Couperin – The Mysterious Barricades.” “That’s it. Catchy little tune isn’t it?”

“You didn’t manage to catch it very accurately.”

“Is that so? Don’t I sing it correctly?” “No. But that fact may have helped to save you from the gallows.” (166-7)

And so it does. The real murderers at Murree are apprehended and the death of Chandler, linked to espionage, is also explained. It also turns out the Sir Francis Cooper was part of the espionage ring. His lovely gramophone concerts had allowed the conspirators to meet. He kills himself on discovery.

The final chapter of the book, chapter 17, is entitled “The Mysterious Barricades.” Here it is in full:

At eight o’clock the following evening Sir Richard sat playing the piano in the Penrose bungalow at Karachi. He had had a pleasant flight down from Delhi that afternoon, and had spent the morning beforehand taking a sentimental farewell to India – watching the dhobies’ bulls go by and the coolies and bullock carts and peasantwomen, and the babus on bicycles belatedly hurrying to their offices. On arrival in Karachi he registered himself at the Sind Hotel, had himself and his luggage weighed, and the luggage labelled and taken to his room

He was pleased that he had been allotted a room in the wing of the hotel other than that in which he had stayed on his previous visit. All the same the sight of a neat card by his bedside announcing arrangements for the next day – times of calling, times for the car, times for the launch – brought back very vividly to him the circumstances of Chandler’s death. He had been glad to get away from the Hotel and its unpleasant memories and to dinner with the Penroses. He had been playing aimlessly for some minutes and it was only the entrance of Mr and Mrs Penrose that brought his mind back to the music. He realised that he had been playing Les Barricades Mysterieuses, and stopped, getting up quickly.

“Please don’t stop,” said Mrs Penrose, “Do go on playing.”

“No, no. I was just playing at random while waiting for you to arrive.”

“Do please finish what you were playing. It sounded a most haunting melody.”

Cherrington sat down again at the piano and played that tune which had in such a curious and remarkable way featured in his life during the last few weeks in India. Yet tonight he could recapture none of the gaiety of the tune: it sounded sinister, cold, menacing, the melody returning again and again as though voicing some supernatural force of inerrant retribution.

He finished playing and the music died away.

“What was that?” asked Mrs Penrose.

“A rondeau. A rondeau by Couperin called Les Barricades Mysterieuses – the Mysterious Barricades. Like so many of Couperin’s titles, we don’t know what this one means. Many people have made guesses.”

“A rondeau,” said Penrose. “It didn’t sound a bit like a rondeau the way you played it. It may “be silly of me, but it gave me a most eerie feeling.”

“Yes,” said Mrs Penrose. “It almost made me shiver.”

Cherrington came over to them from the piano. “You felt that,” he said. “Curious how a man’s mood can come out in the music he plays. I couldn’t help making it sound that way. To me it is now a sinister, tragic tune.”

“Why?”

“Because of that tune,” said Cherrington slowly, ‘because of the Mysterious Barricades I first met a man for whose death yesterday by his own hand I suppose I am largely responsible, whose love for this country had taken recently a curious form. And because of that tune two other people will shortly be condemned to death in Delhi – well because of that and because in a court of law their love for each other will, in the shadow of the gallows, so quickly turn into hate. It is a curious thing isn’t it,” he went on. “That love and hate so quickly turn into each other, as though in the extremes of experience we were nearer to other extremes than we ever imagine. I think that love and hate march along a common frontier too often and too easily crossed. Do you think that it was of those barricades that we must all erect mysteriously in that dread border country of which Couperin was thinking when when he wrote this music – now grave, now gay, now happy and assured, now sinister and terrifying?”

He stopped speaking and there was silence in the room.

Mrs Penrose got up and drew her wrap around her.

“Let us go into dinner,” she said. (182-3)

(In the transcriptions from Daniel’s draft, above, I have silently amended his punctuation, which is somewhat careless. The drawing of Daniel by R. Tolland and the excerpts from his MS are reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of St. John’s College Cambridge.)

Surely one of the strangest and most literal responses to the title of the Couperin piece is the children’s story “The Mysterious Barricades” by the English author of fantasy and supernatural novels and stories, Joan Aiken (1924-2004). The story is in her 1955 collection More Than You Bargained For (London: Jonathan Cape). In a town at the foot of some really tall mountains, there is a small village. One day, the first stranger in ten years, Smith, comes through on a bicycle. He is on the trail of the previous stranger, Jones, who stole his canary and his music and went off into the mountains. Smith finds the canary, whom Jones had sold to a villager for a cup of tea and buys it back for the same price, producing the cup of tea from his pocket. Smith and Jones are both Civil Servants, and Jones was on his way to the Mysterious Barricades, where “Civil Servants go when they retire.” Smith pursues Jones into the fearful mountains, keeping up his courage with the verse junior Civil Servants learn when they first join the Service:

Always helpful, never hurried,

Always willing, never worried,

Serve the public, slow but surely,

Smile, however sad or poorly,

Duty done without a swerve is

Aimed at by the Civil Service.

Finally, following a very narrow path up into the mountains, he finds Jones. Neither is able to turn around or pass the other, so  narrow is the path. Jones, having wandered in the mountains for ten years, sustained only by the buns he pulls from his pocket (he hadn’t risen far enough in the Service to be able to pull out cups of tea and biscuits, as Smith can), he is beginning to doubt the existence of the Mysterious Barricades. Smith suggests they play his Sonata in C Major for two flutes and continuo, the music of which Jones had stolen. Each pulls out a flute and they play. “‘It wants the continuo part’ said Smith sadly.” They play it again and the canary supplies the missing continuo. The Mysterious Barricades open up to receive them. The villagers below never look up, and miss the whole thing. An illustration, by Pat Marriott, accompanies the story. It is reproduced in full size, with some further information, on the Visual Arts page of this site.

narrow is the path. Jones, having wandered in the mountains for ten years, sustained only by the buns he pulls from his pocket (he hadn’t risen far enough in the Service to be able to pull out cups of tea and biscuits, as Smith can), he is beginning to doubt the existence of the Mysterious Barricades. Smith suggests they play his Sonata in C Major for two flutes and continuo, the music of which Jones had stolen. Each pulls out a flute and they play. “‘It wants the continuo part’ said Smith sadly.” They play it again and the canary supplies the missing continuo. The Mysterious Barricades open up to receive them. The villagers below never look up, and miss the whole thing. An illustration, by Pat Marriott, accompanies the story. It is reproduced in full size, with some further information, on the Visual Arts page of this site.

According to the London Times, this story was read aloud at a memorial service for Joan Aiken in 2004. It was also read, by Miriam Margoyles, on the BBC on September 24th, 2006 as part of a series of five stories by Aiken.

The Mysterious Barricades (Douglas, Isle of Man: Times Press, 1964) is a novel by the English musicologist Cedric  Glover. Fans of Peter Schaeffer’s Amadeus will be pleased to learn that the novel is about the legend of Mozart’s murder by Salieri and according to the author’s son, Myles Glover, the original cast of the play were given the novel to read in rehearsal, at the suggestion of Ursula Vaughan Williams. Glover asked Ursula Vaughan Williams (wife of the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams and a prolific poet) to supply some verse for his epigraph. See the Poetry page of this site for the resulting poem.

Glover. Fans of Peter Schaeffer’s Amadeus will be pleased to learn that the novel is about the legend of Mozart’s murder by Salieri and according to the author’s son, Myles Glover, the original cast of the play were given the novel to read in rehearsal, at the suggestion of Ursula Vaughan Williams. Glover asked Ursula Vaughan Williams (wife of the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams and a prolific poet) to supply some verse for his epigraph. See the Poetry page of this site for the resulting poem.

The main character of the novel, a cellist in 1930s London, after hearing a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operatic setting of Pushkin’s verse drama Mozart and Salieri, comes to believe that he is himself a reincarnation of Salieri. He relates a series of events in which people resembling the main characters in the Mozart-Salieri legend play out a kind of parallel to the alleged murder.

The quasi-scientific attitude to the occult and the obsession over making clear the (multiple) means by which the narrative we read was put together give Glover’s novel a strong resemblance to some of the novels of Bram Stoker. The book has many charms and there are passages of very fine writing in it, such as the following, describing the intermission in a performance of Mozart’s Requiem:

I recognized plenty of familiar faces; I had seen the owners countless times and to me they seemed, as it were, part of the trappings of the hall. I could not think of them as having any life apart from it or as following the ordinary avocations of mankind. Some even made tentative signs of recognition as I passed, possibly as a token of appreciation that I, like the programme sellers and the doorkeepers, was at my post. We were all somehow mutually dependent on one another for our enjoyment, though we would have fainted with horror if any one of us had so far forgotten himself as to address a remark to a fellow genius loci. (69)

The significance of the title is explained by a remark in a preface by one of the novel’s characters:

Pitland’s pitiable story goes to show how tenuous are the mysterious barricades which divide clairvoyant perception from hallucination, reality from unreality and sanity from madness. (2)

Myles Glover supplies the following account (in personal correspondence):

My father’s devotion to the Couperin piece dated back to his time as an undergraduate at Balliol College, Oxford before the first World War. He heard it played by the locally prominent Oxford musicologist Dr Ernest Walker at one of the Balliol Sunday evening concerts, and what impressed him was the ghostly quality which Ernest Walker succeeded in giving to it. [An affectionate and amusing letter from Ernest Walker to Glover, written a few years later, can be read here. SE.]

The project for the novel had a long gestation, and was prompted by he himself going to the 1930s performance in London of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Mozart and Salieri’. After serving throughout the second World War in the War Office, my father decided not to resume his business career in shipbroking, even though he was then only 53, and to devote himself instead to writing the novel and his other musical activities.

The novel, for me, has a strong autobiographical tinge, featuring as it does the amateur playing of chamber music, rail journeys on the continent, Pontresina and the Engadine (if I remember rightly) as well as the Alps generally, and the world of opera. My father played the viola in quartets with friends more or less weekly until he became too ill at the end of his life to go on doing so, and he was passionate about rail travel – he planned his holidays himself with the aid of the Cook’s International Time Table and always booked his own accommodation (‘package’ holidays were an anathema to him). The names of the characters in the book are all drawn from the place names of the area in Surrey where we had a weekend house (see below); thus Pitland, one of the two constituent villages making up that of Holmbury St.Mary; Wootton, the home of the diarist, John Evelyn; and Erbsensee (Peaslake).

De gåtfulla barrikaderna (1983) is by a Swedish novelist, Bengt Söderbergh and was published in an English translation as The Mysterious Barricades (London: Peter Owen, 1986; the title in English is a literal translation of the Swedish title). The novel concerns a harpsichordist in France during the middle of the 20th century. An important event for her is her discovery, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, of the only extant manuscript of “Les Barricades Mistérieuses.” She imagines Couperin performing the piece:

With its hesitant notes, despite the fast rhythm and the force in those matt copper tones, ‘The Mysterious Barricades’ managed to catch the mood that must have prevailed at court after the parties were over and Madame de Maintenon had banished all recklessness. The greatest monarch in the world was about to die. The whole of France had been transformed into a deserted hospital, without medicaments or provisions. The cries and torches were thronging the gates. The gangrene went to his heart. Memory, the palace, was committed to memory and the past. The future, tomorrow, was something with which you must not concern yourself.

The spiral is twisting, cogs, butts, springs, in the intricate, perfectly formed mechanism, repeats the same movement again and again. The music oscillates round something not yet expressed, something not yet achieved, something forever repeated. There is one obstacle it cannot escape – one is forbidden from saying more – and against which it does not dare offend. Time exists, time existed, time will exist no more. The man at the harpsichord carries the past like an impediment. The people are there but they don’t speak and they will never meet. There is no hope left. The past belongs to him now, the past is his present. The seductive beautiful song of the past recurs, tries to force itself forward, is pushed back by an invisible obstacle, attacks it with increased tempo, slows down, is pushed back quite close to another vaguely perceptible opening. A last effort. A failure. There is no exit here and, in the reprise, no self-evident repose. (153)

The writing is obscure but the mysterious barricades seem to be keeping separate the past and the present and perhaps, in addition, life and death.

There are three different covers for the book, two associated with the Swedish original, one from the English translation:

|

|

|

Paul Auster‘s novel The Music of Chance (Viking, 1991) gives a prominent role to the piece and its title. The novel’s hero, Jim Nashe, is an amateur keyboard player. At the beginning of the action of the novel, he sells or gives away all his stuff and takes to the road. Before he sells his piano, “he went through several dozen of his favorite pieces, beginning with The Mysterious Barricades by Couperin and ending with Fats Waller’s Jitterbug Waltz, hammering away at the keyboard until his fingers grew numb and he had to give up” (11). Later, owing to bad luck in a poker game, he and Pozzi, a young man he has fallen in with, becomes, in effect, indentured to two millionaires, Flower and Stone, an odd couple who got rich winning the lottery. They have bought a medieval Irish castle which they have shipped, in stones, to their estate in Pennsylvania. Instead of reassembling the stones into the original castle, they decide to build a wall with them:

“A monument, to be more precise,” Flower said. “A monument in the shape of a wall.”

“How fascinating,” Pozzi said, his voice oozing with unctuous contempt. “I can’t wait to see it.”

“Yes,” Flower said, failing to catch the kid’s mocking tone, “it’s an ingenious solution, if I do say so myself. Rather than try to reconstruct the castle, we’re going to turn it into a work of art. To my mind, there’s nothing more mysterious or beautiful than a wall. I can already see it: standing out there in the meadow, rising up like some enormous barrier against time. It will be a memorial to itself, gentlemen, a symphony of resurrected stones, and every day it will sing a dirge for the past we carry within us.”

“A Wailing Wall,” Nashe said.

“Yes,” Flower said, “a Wailing Wall. A Wall of Ten Thousand Stones. (86)

Needless to say, Nashe and Pozzi are the ones who will build it. Much later, while still working at the wall, Nashe resumes his keyboard playing on a small electronic keyboard. He concentrates on

works by pre-nineteenth-century composers: The Notebooks of Anna Magdalena Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, “The Mysterious Barricades.” It was impossible for him to play this last piece without thinking about the wall, and he found himself returning to it more often than any of the others. It took just over two minutes to perform, and at no point in its slow, stately progress, with all its pauses, suspensions, and repetitions, did it require him to touch more than one note at a time. The music started and stopped, then started again, then stopped again, and yet through it all the piece continued to advance, pushing on toward a resolution that never came. Were those the mysterious barricades? Nashe remembered reading somewhere that no one was certain what Couperin had meant by that title. Some scholars interpreted it as a comical reference to women’s underclothing—the impenetrability of corsets—while others saw it as an allusion to the unresolved harmonies in the piece. Nashe had no way of knowing. As far as he was concerned, the barricades stood for the wall he was building in the meadow, but that was quite another thing from knowing what they meant. (181)

Flower’s claim that “every day [the wall] will sing a dirge for the past we carry within us” echoes the reactions of Ursula Vaughn Williams and Bengt Söderbergh noted above that the mysterious barricades have something to do with the disjuncture between past and present or past and future.

In an interview, Auster has said that the book was originally going to be entitled The Mysterious Barricades:

It’s funny, I originally had a different title for that book. It was called The Mysterious Barricades, which was the title of the Couperin piece that Nashe plays in the book. I never liked it as a title for the book, but it was the only one I had. I must have been two-thirds of the way through the book before I found The Music of Chance. I was waiting in line at the supermarket. It just came to me.

(And a rock band in David Mitchell’s novel Ghostwritten takes its name, “The Music of Chance,” from the title of Auster’s novel, so if the novel had been called The Mysterious Barricades, who knows but that the band in Mitchell’s book might have been so called too!)

This novel is far from the only connection between Auster and Couperin’s piece. A poetry journal entitled The Mysterious Barricades, edited by Christine Berl, Allen and Andra Kimball, and Henry Weinfield, was published from 1972 to 1976. Auster published something in the journal. The piece is also referred to by Auster in his novel Moon Palace (1990). The narrator, Marco Fogg, is travelling across country with a man who turns out to be his father:

Later on, when the sun began to go down, we spent more than an hour enumerating our preferences in every area of life we could think of: our favorite novels, our favorite foods, our favorite ballplayers. We must have come up with more than a hundred categories, an entire index of personal tastes. I said Roberto Clemente, Barber said Al Kaline. I said Don Quixote, Barber said Tom Jones. We both preferred Schubert over Schumann, but Barber had a weakness for Brahms, which I did not. On the other hand, he found Couperin dull, whereas I could never get enough of Les Barricades Mystérieuses. He said Tolstoy, I said Dostoyevsky. He said Bleak House, I said Our Mutual Friend. Of all the fruits known to man, we both agreed that lemons smelled the best. (290)

Fogg’s liking for the Couperin echoes earlier language in the narrative, where he speaks of crossing “some mysterious boundary deep within myself” (213) or of “gain[ing] entrance past the mute surfaces of things” (230).

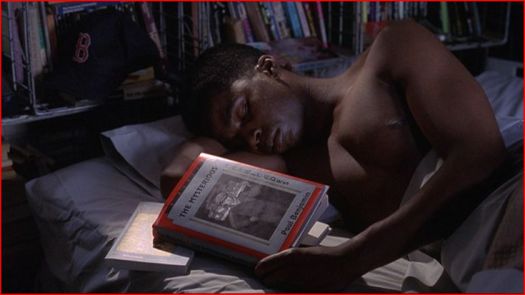

Finally, in the Wayne Wang film Smoke (1995), for which Auster wrote the screenplay, one of the main characters is an author Paul Benjamin. In one scene, we see another character, Rashid, asleep with one of Benjamin’s novels in his hand. The novel is entitled The Mysterious Barricades:

Helmi Nyström, of Finland, has a dissertation, entitled Three Sides of a Wall – Obstacles and Border States in Paul Auster’s Novels, which discusses the passages quoted above and the theme of walls and barriers in Auster’s work more generally.

William Wharton‘s novel Last Lovers (New York, 1991) tells the story of an American businessman, Jack, living in Paris, who leaves his family and his job to live as a homeless painter. By chance, he meets Mirabelle, a woman in her sixties who has suffered from hysterical blindness since she was a child. Though blind, Mirabelle has acquired, and taught herself to play, a harpsichord. As she and Jack, or Jacques as she calls him, becomes friends, and then lovers, she plays for him. On the first occasion, she plays a suite by Louis Couperin. Later, she plays “Les Barricades Mistérieuses” (I try to reproduce the author’s use of font to indicate the different characters):

“Now we should stop and go to bed. But first, after all that Bach, I should like to play one of my very favorites from Monsieur François Couperin. There are eight morceaux, and this is the fifth piece in the sixth ordre. It is called ‘Les Barricades Mistérieuses.’ This would be called ‘The Mysterious Barricades’ in English, I believe. I think of my affliction sometimes as my personal barricade mistérieuse, perhaps this is why I like to play this one so much. Listen.”

She begins to play. I know the work but I’d never heard it played as Mirabelle plays it. There is the deep, dark mystery of the unknown. I can almost experience her blindness in those sections. The contrast with the lighter sections is strong and the continual recurrence of the low tones is beautifully executed. I’m enthralled. I almost lose contact. Then she is finished. I get up, turn on the light, go over, and put my arms around her from behind. She clasps her hands over mind. They are warm and must be tired. (315-6)

Jack Anderson‘s Traffic (Minneapolis: New Rivers Press, 1998) reprints a prose-poem of his called “The Mysterious Barricades: or, The Enchaînments of Memory,” which originally appeared in the magazine Chelsea. A sub-title to the piece reads “A Free Fantasia on Themes from the Ballet To the Ghost of Joseph Cornell,” and, true enough, Anderson’s piece picks up on one of Joseph Cornell’s wonderful boxes, Taglioni’s Jewel Casket (1940). The box contains glass jewels and cubes (that resemble ice-cubes). On the inside of the top there is the following text:

On a moonlight night in the winter of 1835 the carriage of Marie TAGLIONI was halted by a Russian highwayman, and that enchanting creature commanded to dance for this audience of one upon a panther’s skin spread over the snow beneath the stars. From this actuality arose the legend that to keep alive the memory of this adventure so precious to her, TAGLIONI formed the habit of placing a piece of artificial ice in her jewel casket or dressing table where, melting among the sparkling stones, there was evoked a hint of the atmosphere of the starlit heavens over the ice-covered landscape.

Anderson’s prose-poem tells the story of Taglioni and the highwayman but with crucial differences of detail. The story is told by a Russian ballet teacher in Milwaukee, who claims it was handed down over the generations by teachers and students at the Imperial Russian Ballet School in St. Petersburg. In this version of the story, the highwayman prevents Taglioni from escaping by creating barricades across the road comprising the female corps de ballet accompanying her. Also traveling with her is the composer Couperin (which, of course, dates Anderson’s version to over a hundred years before Cornell’s). On returning to Paris, he composes “The Mysterious Barricades” as “a musical memento of that remarkable adventure.”

An entire, though short, chapter from Camille Laurens‘s Dans ces bras-là (2000) is devoted to the piece, and what it says about difficulties in personal relations between the sexes. I quote the chapter, “Alone with him,” from the 2004 translation by Ian Monk, In His Arms: A Novel:

Men are separated from women forever.

Just listen to Couperin’s music, for example, Les Barricades Mystérieuses. The piece lasts only about two minutes… It’s shorter than a love song but it says it all, clear as crystal: I try, I approach, I come, I come back, the air trembles, I say this and that, the same thing or practically, always rephrasing it, shading it, repeating it—I love you, maybe; but hang on, someone’s stopped me, who goes there, who are you, who on earth are you?—silence falls, the mystery remains.

Man and woman: mysterious barricades. A lesson in shadows, if you can learn from the night. (204)

Kathryn Davis‘s Versailles: A Novel (2002) reimagines the life of Marie Antoinette. The following passage represents her drumming on the arm of her chair, recalling playing the Couperin piece as a child:

My eyes failing but my ears still perfect—I could hear every whisper. Oho, look at her now, the bitch. That’ll teach her to steal our food. But why is she drumming like that on the arm of the chair?

My mother stifling a yawn as my fingers flew across the keys of the clavichord. Les Barricades Mystérieuses. François Couperin. Sit straighter, Antonia. Do you want to end up with a hump?

To which the answer of course is no no no no no, unless to avoid it you have to die before the age of forty. (200)

Others, too, have made a connection between the Couperin piece and Marie Antoinette. See Sarah Loven’s photo Les Barricades Mistérieuses (Visual Arts page) and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (Film page).

The protagonist of Edmund White‘s story “A Good Sport” (originally in The Yale Review, vol 95, no. 3, 2007 and then, in the same year in White’s Chaos: A Novella and Stories) says:

For a year or two I took up the harpsichord just so I could play Scarlatti’s Sonata K 24 and Couperin’s “Les Barricades mystérieuses.” (151)

Patrick Modiano‘s 2007 novel Dans le café de la jeunesse perdue (Editions Gallimard), recently published in English as In the Cafe of Lost Youth (New York; New York Review Books, 2016) is set in the mid- to late 1950s or early 1960s. Speaking of the eponymous cafe, it says,

Often, the regulars of the Conde had books with them that they would set down nonchalantly on the table before them, the covers stained with wine. The Songs of Maldoror, Illuminations, The Mysterious Barricades. (12)